Essentials

Diagnosis is the process of determining the nature and cause of disease or injury through the evaluation of patient history, examination, further investigative tests and review of laboratory data.

Lyme disease should be a clinical diagnosis based on:

- History of tick exposure, tick bite and any risk factors, eg outdoor leisure activities or occupation, which increase the likelihood of contact with ticks.

- Clinical symptoms and how these developed.

- Any evidence of an erythema migrans rash.

- Physical signs on examination eg facial palsy, radiculitis, meningoencephalitis.

- Diagnostic tests.

- Treatment received- especially prior antibiotic or immunosuppressant treatment which may affect Lyme serology test results.

How is Lyme Disease Diagnosed?

- By recognising the typical rash, called erythema migrans (EM).

- By recognising typical symptoms following a known tick bite.

- By suspecting possible Lyme disease and confirming this with a blood test.

“Diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis is based on characteristic clinical signs and symptoms, complemented by serological confirmation of infection once an antibody response has been mounted.“[1]

However, as in much of medicine, it is sometimes not that simple!

Because there is no definitive test for disease activity, and no test that can rule out Lyme disease, LDA believes that clinical judgement is vital when assessing patients and interpreting the results of any tests. It is important to recognise typical symptoms and signs, though these may overlap with many other conditions, which complicates diagnosis.

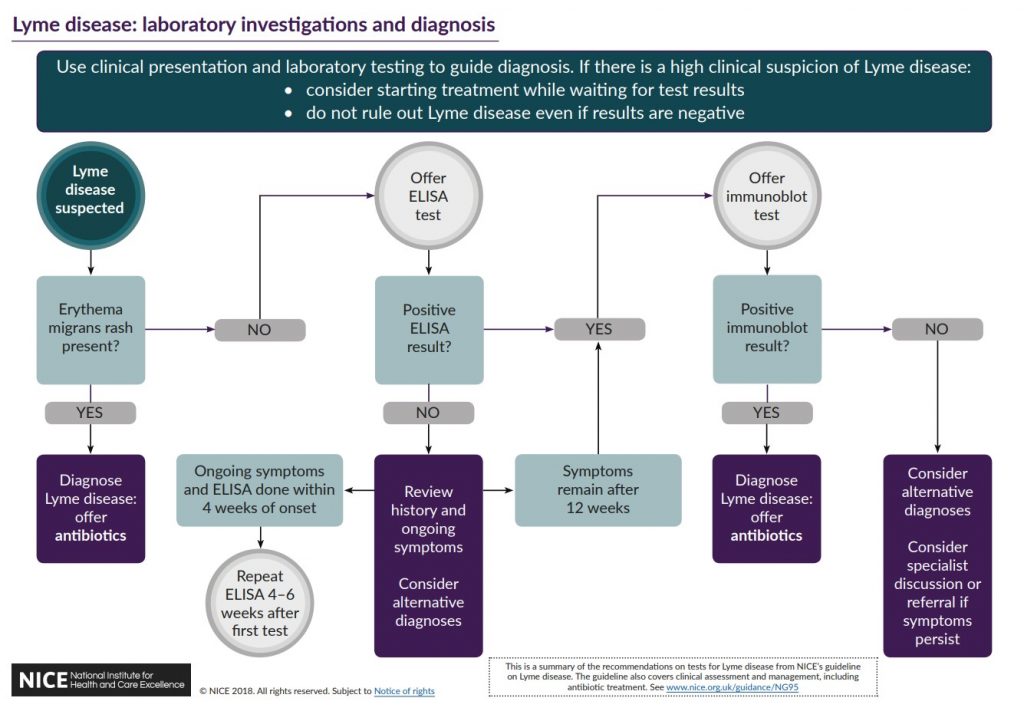

The NICE Guideline, has the following flowchart

So before you get to tests, how do you suspect Lyme disease?

Lyme disease with a rash

In approximately two thirds of UK cases, the patient notices a rash. The erythema migrans rash (EM), as it is called, appears on average about 2 weeks after the tick has detached or was removed (range 1-129 days). The rash may be mildly painful or itchy but is usually not. It may remain for several weeks gradually enlarging.[2]

Be aware that an infected insect bite can look like the EM rash, but is usually hot to the touch and itchy; it also tends to fade in a few days.

The EM rash is diagnostic of Lyme disease and treatment should start immediately without waiting for blood test results, which are likely to be negative at this early stage, even if there are other symptoms too.

Without appropriate treatment Lyme disease may spread to other parts of the body as described below.

Lyme disease: other symptoms and signs

When a rash has not been seen, symptoms (what the patient feels like) and signs (visible signs) should be considered, along with any tick bites, or exposure to ticks.

What was the person doing a couple of weeks before they fell ill? Holiday in Europe? Camping or gardening perhaps?

The most common symptoms in adults are ‘flu like symptoms of aching, low fever, headache and fatigue, but symptom patterns vary from person to person.[3]

The most common symptoms in adults are ‘flu like symptoms of aching, low fever, headache and fatigue, but symptom patterns vary from person to person.[3]

Mild symptoms may have passed, without a visit to the GP, to be replaced by other symptoms.

See here for a list of symptoms and signs that have been associated with Lyme disease.

Facial palsy in children with headache and fever has been shown to predict early Lyme neuroborreliosis during peak Lyme season in endemic areas (April – Oct).[4]

A UK paper from Southampton University Hospital states

“In areas endemic with Lyme disease, Lyme disease should be considered as the likely cause of facial nerve palsy in children until proven otherwise. All children presenting with FNP to health care providers in these areas should have Lyme serology tested and empirical treatment for Lyme initiated pending the results of tests.” [5]

NICE Guideline, section 1.2.4, states:

Consider the possibility of Lyme disease in people presenting with symptoms and signs relating to 1 or more organ systems (focal symptoms) because Lyme disease is a possible but uncommon cause of:

- neurological symptoms, such as facial palsy or other unexplained cranial nerve palsies, meningitis, mononeuritis multiplex or other unexplained radiculopathy; or rarely encephalitis, neuropsychiatric presentations or unexplained white matter changes on brain imaging

- inflammatory arthritis affecting 1 or more joints that may be fluctuating and migratory

- cardiac problems, such as heart block or pericarditis

- eye symptoms, such as uveitis or keratitis

- skin rashes such as acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans or lymphocytoma.

According to some studies, Lyme neuroborreliosis may occur in nearly a quarter (15-25%) of UK cases.[6,7]

Also from the NICE Guideline, section 1.2.13:

If there is a clinical suspicion of Lyme disease in people without erythema migrans:

- offer an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test for Lyme disease and

- consider starting treatment with antibiotics while waiting for the results if there is a high clinical suspicion.

Because the blood tests rely on development of specific antibodies, and these take time to develop, NICE emphasises “Do not rule out diagnosis if tests are negative but there is high clinical suspicion of Lyme disease.” Once a course of treatment has started, it makes sense to continue it.

NICE has a diagram showing the route from suspicion of possible Lyme disease, to the different tests, to diagnosis.

References

- Lyme borreliosis : diagnosis and management. Kullberg, B. J., Vrijmoeth, H. D., Schoor, F. Van De, & Hovius, J. W. R. (2020). British Medical Journal, 2019(369), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1041

- Clinical characteristics associated with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato skin culture results in patients with erythema migrans. Strle, F. et al. (2013). PloS One, 8(12), e82132. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0082132

- Lyme disease in the U.K.: clinical and laboratory features and response to treatment. Dillon, R., O’Connell, S., & Wright, S. (2010). Clinical Medicine (London, England), 10(5), 454–457. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21117376

- Clinical predictors of Lyme disease among children with a peripheral facial palsy at an emergency department in a Lyme disease-endemic area. Nigrovic et al. (2008)Pediatrics, 122(5), e1080-5.

- High frequency of paediatric facial nerve palsy due to Lyme disease in a geographically endemic region. Munro et al. (2020) International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 132, 109905.

- Lyme disease surveillance in England and Wales, 1986-1998. Smith R, O’Connell S, Palmer S. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6(4):404–7

- Neuroborreliosis in the South West of England. Lovett JK, Evans PH, O’Connell S, Gutowski NJ. Epidemiol Infect. 2008 Dec;136(12):1707–11.

Printer Friendly

Printer Friendly