Essentials

-

- Ticks are found across the UK in both town and countryside

- Most UK ticks do not carry infection – infection rate in any place in the UK varies from zero to about 1 in 5 ticks (8)

- Infection rates of ticks in Europe are higher

- Ticks can be as small as a full stop, or poppy seed, and can go unnoticed

- The ticks you see on pets are larger, because they are adult ticks and have swollen with blood from the pet.

- Ticks are most active March to October, but they can be active on mild winter days

- You will not feel the tick attach to you, so check your skin and that of children

- Remove a tick properly, without squashing it

- Meet Tina the tick in this 12 minute video for all the essential facts – informative, funny and brilliant photography.

What are ticks?

Ticks are related to spiders, mites and scorpions. There are many different species of tick living in Britain, each preferring to feed on the blood of different animal hosts. The one most likely to bite humans in Britain is the Sheep tick, or Castor Bean tick, Ixodes ricinus. Despite its name, the sheep tick will feed from a wide variety of mammals and birds.

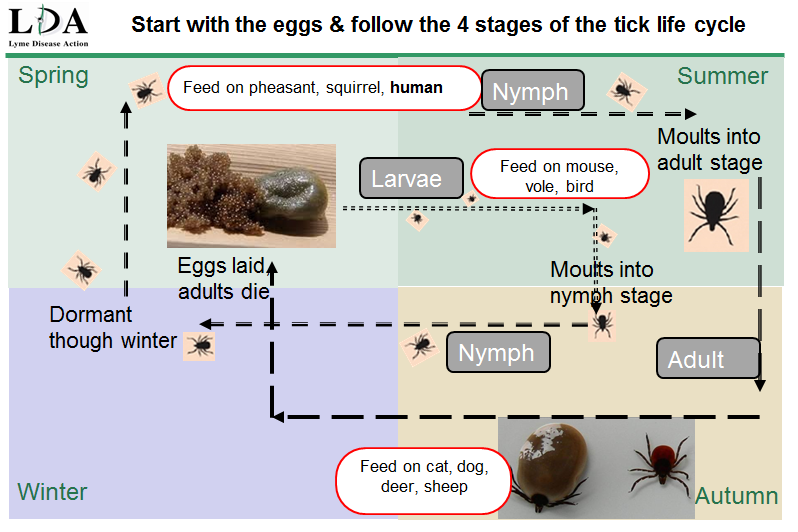

There are four stages to a tick’s life-cycle: egg, larva, nymph, and adult. Larvae, nymphs and adults spend most of the time on the ground protected by leaf litter, leaving this protection to find a meal. They feed only once in each stage, staying attached for a few days, then dropping to the ground to moult into the next stage. The adult male dies after mating. When the adult female finishes feeding it drops to the ground, releases eggs and dies.

The whole life cycle from egg to adult lasts around 2 years.

To the naked eye the larvae look like tiny pale spiders, not much bigger than a full stop. Nymphs are slightly larger and darker, poppy seed size. Larvae have six legs and nymphs and adults eight. It is the nymph which is most likely to bite you.

To see what an adult tick looks like in motion, watch this brief video. Public Health England have produced a longer 3 minute video with some very good images of ticks.

Bites from other ticks are possible. Public Health England’s Tick Surveillance Scheme (6) has reported the following ticks collected from humans:

- the Hedgehog tick, Ixodes hexagonus, the second most common tick detected. Mostly found on dogs, cats and hedgehogs;

- the Passerine tick, Ixodes frontalis, normally found on birds, but occasionally on humans;

- the Ornate Cow Tick Dermacentor reticulatus. This tick is currently only recorded in W Wales, N&S Devon and Essex – mainly in coastal sand dunes and marsh, but recently in Essex grassland (5). It carries canine babesiosis which is a risk to dogs, and it is implicated in transmission of Tick-borne Encephalitis (TBE). This tick has ornate markings on its back and is often pictured in UK newspapers, despite its rarity in the UK!

- The Red Sheep Tick Haemaphysalis punctata found on the South Downs, Kent (Isle of Sheppey) and Essex (Dendie Peninsula). Mostly found on horses and humans (7);

These are amongst the 20 tick species recorded as endemic to the UK. Most of them are specialist parasites of wildlife, but do occasionally find their way onto pets and humans.

There are different ticks in other parts of the world and they carry different diseases. If you take your dog abroad, be aware of this and take suitable precautions. The Brown Dog Tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus has been brought into the UK from Europe on dogs and can survive and reproduce inside a home, unlike the native UK ticks.

In the USA the highest risk comes from the Deer tick, Ixodes scapularis, but this is not known in Europe.

Where can they be found?

Ticks can be found in any place with moist air where they are protected from drying out –

“I. ricinus is sensitive to climatic conditions, requiring a relative humidity of at least 80% to survive during its off-host periods, and is therefore restricted to areas of moderate to high rainfall with vegetation that retains a high humidity (i.e. litter layer and soil remain humid during the day). Typical habitats vary across Europe, but typically include deciduous and coniferous woodland, heathland, moorland, rough pasture, forests and urban parks.”[1]

Ticks can also be found in private gardens, especially those with shady shrubberies or deep vegetation and a strong local wildlife population.

Numbers vary from place to place and from year to year, but ticks can be found across the UK [2]. Not all ticks carry disease, and infection rates in any one place may fluctuate from year to year.[3]

See Dr Sarah Randolph’s presentation at our 2008 conference: How does tick ecology determine risk?

How do they pass on disease?

Ticks feed on the blood of other animals. If a larval tick picks up an infection from a small animal such as a mouse, when it next feeds (as a nymph) it can pass the infection to the next animal or human it bites.

They cannot jump or fly, but when ready for a meal will climb a nearby piece of vegetation and wait for a passing animal or human to catch their hooked front legs. This behaviour is known as questing. The tick will not necessarily bite immediately, but will often spend some time finding a suitable site on the skin, so it is important to brush off pets and clothing before going inside.

Once a tick has started to feed, its body will become filled with blood. Adult females can swell to many times their original size. As their blood sacs fill they generally become lighter in colour and can reach the size of a small pea, generally grey in colour. Larvae, nymphs and adult males do not swell as much as they feed, so the size of the tick is not a reliable guide to the risk of infection. If undisturbed, a tick will feed for around 5 to 7 days before letting go and dropping off.

The bite is usually painless and most people will only know they have been bitten if they happen to see a feeding tick attached to them.

The risk of bacterial infections increases the longer the tick is attached, but can happen at any time during feeding. Viruses can be passed immediately. As tick bites are often unnoticed, it may be difficult to determine how long it has been attached. Any tick bite should be considered as posing a risk of infection although the risk in the UK is low.

Antibiotic treatment “in case” of disease (known as prophylaxis) is not recommended: see our self help page. The small red mark left by the tick will fade over a few days, but see your GP if any symptoms of illness develop over the next couple of weeks.

Adult people are most often bitten around the legs. Small children are generally bitten above the waist—check their hairline and scalp.[4]

The UK Health Security Agency website has some useful pages on ticks including a video and details of their tick recording scheme.

What diseases do ticks carry?

There are several diseases that can be caught from a tick bite in the UK – see our separate page on other tick-borne diseases.

Globally, the list of diseases carried by ticks is much longer.

Some ticks carry more than one disease at the same time but it is not known how often this happens in the UK. Co-infection may have an impact on human disease and there is a need for more research into this aspect [9].

References

1. Medlock et al. “Driving forces for changes in geographical

distribution of Ixodes ricinus ticks in Europe”. Parasites & Vectors 2013, 6:1

2. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/tick-surveillance-scheme

3. Bettridge et al. “Distribution of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes ricinus Populations Across Central Britain”. Vector borne and zoonotic diseases. 2013 Feb 19;13(X)

4. Robertson JN, Gray J, Stewart P. “Tick bite and Lyme borreliosis risk at a recreational site in England.” Eur J Epidemiol. 2000;16(7):647–52.

5. Medlock JM, et al. Distribution of the tick Dermacentor reticulatus in the United Kingdom. Med Vet Entomol. 2017;(April).

6. Hansford, Kayleigh M., et al. 2022. Mapping and Monitoring Tick (Acari, Ixodida) Distribution, Seasonality, and Host Associations in the United Kingdom between 2017 and 2020. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 2022 1 (12).

7. Medlock JM et al Has the red sheep tick, Haemaphysalis punctata , recently expanded its range in England? Med Vet Entomol. 2018 Sep 8;32(4).

8. Hansford et al Ticks and Borrelia in urban and peri-urban green space habitats in a city in Southern England. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016.

9. Cutler, Sally J, et al. “Tick-Borne Diseases and Co-Infection: Current Considerations.” Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases 2021 12 (1). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2020.101607.

Printer Friendly

Printer Friendly