Essentials

- Lyme Neuroborreliosis (LNB) is Lyme borreliosis (Lyme disease) affecting the nervous system;

- LNB can be difficult to diagnose unless it presents with typical symptoms and clinicians actively consider this diagnosis;

- LNB can affect any part of the nervous system, including the brain, if left untreated;

- it causes a wide range of neurological and psychiatric disorders;

- the pattern of symptoms, and how the disease progresses, varies from patient to patient;

- slow thinking (brain fog) can be due to fatigue caused by Lyme disease and is not necessarily LNB;

- there is no gold standard test that can be relied upon for diagnosis;

- LNB can be successfully treated if treatment starts early;

- antibiotics are required with good penetration of body tissue and spinal fluid;

- the NICE Guideline and European guidelines acknowledge the limited evidence on which to base treatment recommendations.

What are the symptoms of Lyme Neuroborreliosis?

After what is often a flu-like start to the infection, patients may develop early neurological problems.[1] Lyme neuroborreliosis (LNB) may affect

- the peripheral nervous system involving the motor and sensory nerves, including the facial nerve.

- the central nervous system, which is the brain and spinal cord;

Infection of the peripheral nerves is more common and the following symptoms can occur relatively early in disease:

- Inflammation of motor or sensory spinal nerve roots – radiculitis. This may cause weakness eg foot-drop or paralysis. Common sensory symptoms include sharp pain which may be severe and often worse at night, or feelings such as tingling, itching or numbness.

- inflammation of the nerves in the head which emerge directly from the brain – cranial neuritis. Most commonly the facial nerve causing facial palsy with weakness or paralysis on one or both sides of the face. Involvement of other cranial nerves may cause double vision, drooping eyelid, numbness, pain and tingling of the face, hearing loss, dizziness and tinnitus.

- inflammation of the membranes which surround the brain and spinal cord – meningitis. Symptoms may include headache, neck stiffness and sensitivity to light. This is less severe than the bacterial meningitis caused by other organisms.

This trio of affected areas is known as “Bannwarth’s Syndrome” and was recognised in Europe in the 1940s before the cause of Lyme disease in the USA was discovered by Willy Burgdorfer.

Inflammation affecting lower parts of the brain and spinal cord may cause problems with the autonomic nervous system which controls bodily functions such as blood pressure and heart rate. This can lead to difficulty when standing.

A patient will have one or several of the above symptoms. There are many other possible symptoms – see our detailed leaflet on Lyme Neuroborreliosis.

Central nervous system complications are said to be rare and include

- brain inflammation (encephalitis);

- spinal cord inflammation (myelitis);

- cerebral blood vessel inflammation (vasculitis).

These patients are likely to very unwell and admitted to hospital for investigations.

How is LNB diagnosed?

In common with all different forms of Lyme disease, diagnosis is by recognising clinical symptoms, assessing test results and ruling out other conditions.[2]

European guidelines [3] specify that that there must be abnormalities in the spinal fluid to confirm definite LNB, though rather confusingly it is recognised that Bannwarth’s syndrome is still LNB although it may only affect the peripheral nervous system and the spinal fluid may not contain antibodies to Borrelia. In practice, this maybe doesn’t matter to the patient, as long as treatment is started and the patient gets better. A lumbar puncture to take spinal fluid for analysis is invasive and doctors must question whether it is necessary in those cases where the blood test is a clear positive and the symptoms are a clear indicator.

Analysis of spinal fluid can, however, test for antibodies to the Borrelia bacteria and this can help to distinguish LNB from other neurological conditions when the diagnosis is unclear.

What is the treatment for LNB?

The NICE Guideline differentiates between

- LNB affecting only the cranial nerves or peripheral nervous system – doxycycline 200mg/day, as in early Lyme borreliosis

- LNB affecting the central nervous system – intravenous ceftriaxone or doxycycline 400 mg/day (ie double the usual doxycycline dose)

See the Uncertainties section at the bottom of this page.

Diagnosis and management of children

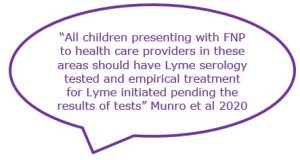

Facial nerve palsy (FNP) with headache and fever has been shown to predict early LNB in children during peak Lyme disease season [4]. Anxiety, emotional disorders and difficulties with attention and learning may develop if LNB is undetected or untreated.

Small children may only have non-specific symptoms such as loss of appetite, fatigue, headache and behavioural problems.

It is important to realise that LNB can progress fast in children, leading to central nervous system disease when a neurological examination is still normal [5] and before a lumbar puncture is positive for LNB. The NICE Guideline, section 1.3.2, says that the diagnosis and management of children under 18 should be discussed with a specialist as children may need treatment with IV antibiotics.

See our news article on a recent paper about facial palsy in children from Southampton Hospital.

Uncertainties

- Research in Europe has mainly studied early LNB. The treatment of late diagnosed LNB is uncertain as there have been no good quality European trials. It is unclear whether ‘standard’ treatment for early uncomplicated illness will treat more complex disease.

- It seems possible that inflammation may affect the brain without the bacteria having crossed into the spinal fluid [7].

- It is unclear whether longer term or re-treatment is helpful. Several case studies suggest this may be so [6].

- It is unknown whether continuing symptoms after ‘standard treatment’ are due to persistent infection, immune activation or tissue damage.[2] It may be prudent to treat patients on a pragmatic basis pending further research.

For more detailed information on LNB symptoms and tests, download our leaflet Lyme Neuroborreliosis. The web version has been arranged to fit onto two double-sided sheets of A4 paper for easier home printing.

References:

- Nordberg C.L et al. Lyme Neuroborreliosis in Adults: A Nationwide Prospective Cohort Study. Ticks and Tick-Borne Diseases 2020 11 (4): 101411.

- Kullberg B.J et al. Lyme Borreliosis : Diagnosis and Management. British Medical Journal 2020 (369): 1–20.

- Mygland A et al. EFNS guidelines on the diagnosis and management of European Lyme neuroborreliosis. Eur J Neurol 2010 Jan 17(1):8–16, e1-4.

- Nigrovic LE, Thompson AD, Fine AM, Kimia A. Clinical predictors of Lyme disease among children with a peripheral facial palsy at an emergency department in a Lyme disease-endemic area. Pediatrics 2008 Nov;122(5):e1080-5.

- Broekhuijsen-van Henten DM, Braun KPJ, Wolfs TFW. Clinical presentation of childhood neuroborreliosis; neurological examination may be normal. Arch Dis Child. 2010 Nov ;95(11):910–4.

- Kortela E, etal. Cerebral vasculitis and intracranial multiple aneurysms in a child with Lyme neuroborreliosis. JMM Case Reports. 2017;4(4):1–6.

- Eckman EA, Pacheco-Quinto J, Herdt AR, Halperin JJ. Neuroimmunomodulators in Neuroborreliosis and Lyme Encephalopathy. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;

Printer Friendly

Printer Friendly